Unveiling the Nuu Savi's Cultural Journey: Rematriation and Beyond

Claiming Their Legacy: The Reemergence of Our Forebears

The dance of life has been intricately choreographed by our human ancestors, who left behind a rich tapestry of culture, shaping their legacy through artifacts and stories. From the stone age to the digital age, Indigenous Peoples have etched their stories on materials like wood, palm, clay, bone, and skin, creating a living link between material culture and our heritage.

These precious pieces, however, have often been uprooted, sending fragments of a People’s history spiraling across the globe. In museums, academic institutions, and private collections, these objects are frequently cataloged as "objects of curiosity" and bullied into silence, belittling their true significance. Simultaneously, in our homes, these treasures lay undiscovered, forgotten in the shadows of a colonial education designed to erase our roots.

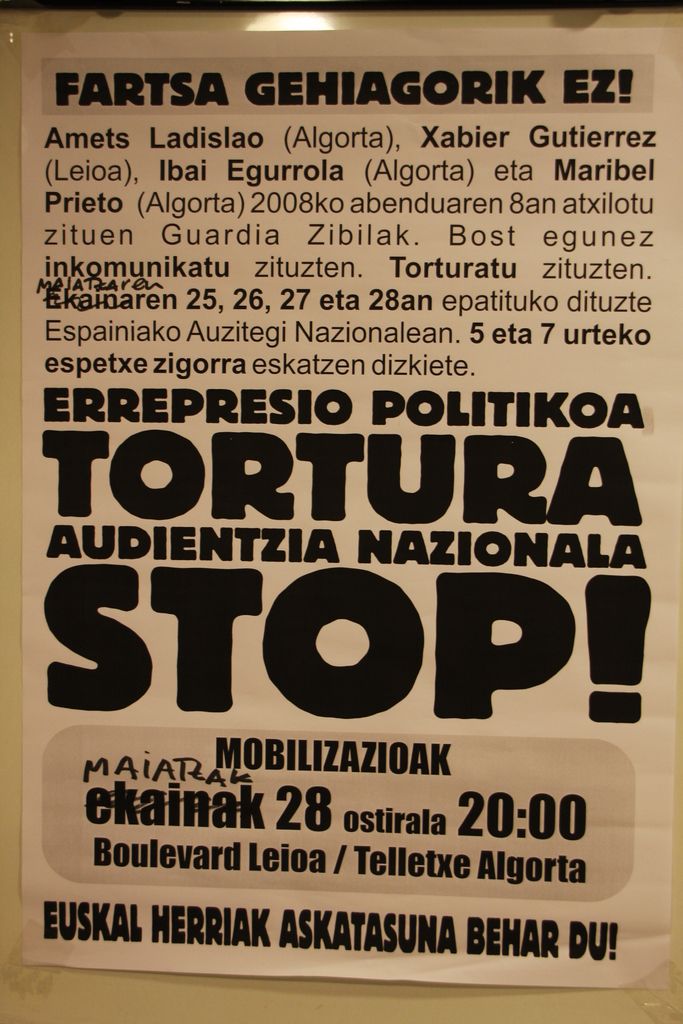

The rematriation of Indigenous cultural heritage serves as a bridge, connecting these scattered fragments to their original homes. It is a battle cry for justice and human rights, echoing through Indigenous communities globally. The movement was ignited in the late 1960s, when Native Americans demanded the rehumanization of their ancestors' remains. They called out the desecration of sacred sites and graves, challenging the archaeological community that excavated and presented Indigenous heritage as commodities. An act of defiance against the oppressive forces of colonialism, this movement set the stage for a struggle towards decolonization.

A glimpse into the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C.

Rematriation transcends ethics and morals, symbolizing a collective right proclaimed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It represents a form of postcolonial reparation and can be seen as a social relationship in itself. Today, countries like the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Chile are making strides in recognizing the importance of rematriation, acknowledging it as a right enshrined within the United Nations Declaration.

This recognition, however, does not yet have binding legal status, but it signifies critical advancements that echo across Indigenous communities demonitizing their struggle for the return of their cultural artifacts and ancestral remains. The remains of our ancestors are emotionally, spiritually, and physically significant, stripped from their context and studied without regard for their sanctity.

A Dance Between Ethics and Empowerment

Distinguishing rematriation from restitution is essential. In rematriation, Indigenous peoples take center stage, advocating for recognition of their cultural rights. In contrast, restitution involves governments negotiating the fate of artifacts. Rematriation is a journey of reclaiming heritage and empowering our communities, while restitution is a process of restoring stolen goods.

The current legal landscape often overlooks Indigenous rights, recognizing states as the legitimate owners of cultural assets, ignoring the living relationship that Indigenous peoples have with their ancestors. Although the presence of Indigenous peoples in Mexico is undeniable, addressing the rematriation of ancestral remains and cultural elements remains challenging in the face of state interests.

Embracing our Roots: The Nuu Savi and the Dance of Rematriation

The Nuu Savi, also known as the Rain People, inhabiting the northeastern regions of Oaxaca, Puebla, and Guerrero, Mexico, have been shaped by a rich history and a cultivated material cultural legacy. With languages spanning 81 variants and a civilization marked by immense cultural wealth, the Nuu Savi continue to strive for the rematriation of their cultural heritage.

Centuries of colonial exploitation and isolation have left our cultural treasures scattered and disconnected from their origins. Our ancestors' stories are hidden in the shadows of museums and institutions, divorced from their cultural and spiritual context. It is important to restore these stories to their rightful place, enriching our identity and rekindling our connection with our past.

The journey of rematriation requires the active participation of the Nuu Savi and a collective effort between our people, government, institutions, museums, and organizations. It is a dance that demands patience, collaboration, and a unified determination to reclaim our history and safeguard our heritage.

Omar Aguilar Sánchez's lens capturing the essence of Nuu Savi culture

As the world moves towards a more interconnected future, it is essential that we embrace and celebrate the unique identities of Indigenous communities like the Nuu Savi. Empowering the return of our cultural heritage will help us strengthen our cultural identity, build a sense of community, and ultimately remind future generations of the dances that started it all.

--Izaira López Sánchez (Ntyivi Ñuu Savi) is Project Coordinator at the Americas Research Network (ARENET) and the driving force behind the Nuu Savi Collections Around the World Project.

A glimpse of the vibrant Tu’un Savi language in San Pedro Teozacoalco, Oaxaca, Mexico

- Embracing our roots, the Nuu Savi continue to strive for education and self-development, seeking the restoration of their cultural heritage through lifelong learning and the rematriation of their cultural artifacts.

- This journey of reclaiming heritage and empowering the Nuu Savi community represents not just a battle for the return of their cultural treasures, but also a lifelong commitment to learning about their past and preserving their identity for future generations.