Liberation's Poetic Essence: A Hypothetical Collection (of Thoughts and Artifacts)

As an artist delving into various dialects, I'm always on the hunt for the least bitter taste to settle on. Based in Tanzania, my work revolves around Tanzanian heritage and human remains locked away in Germany's archives.

I'm not here to correct historical wrongs or seek revenge. Time has passed, and what's lost can't be fully regained. I don't provide solutions or offer solace. Instead, I offer a space for various poems, a voice reading them, and a commitment to connect with this troubled history. Along with fellow scholars and poets, I evoke diverse realities of the brutal past, with its atrocities, trafficking, oppression, and disrespect, without relying on the murderer's notes for an account of the murdered.

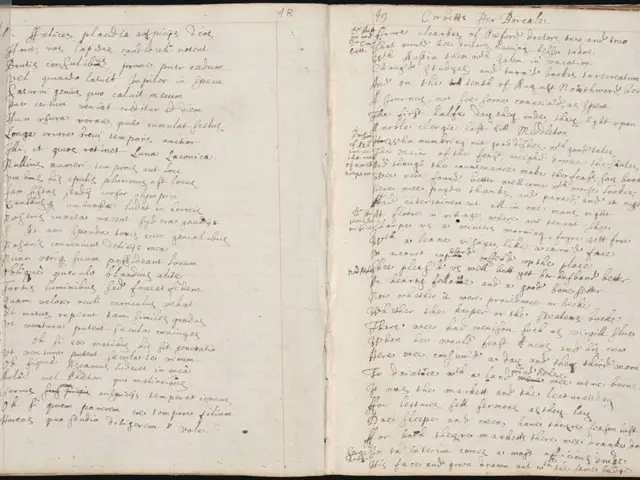

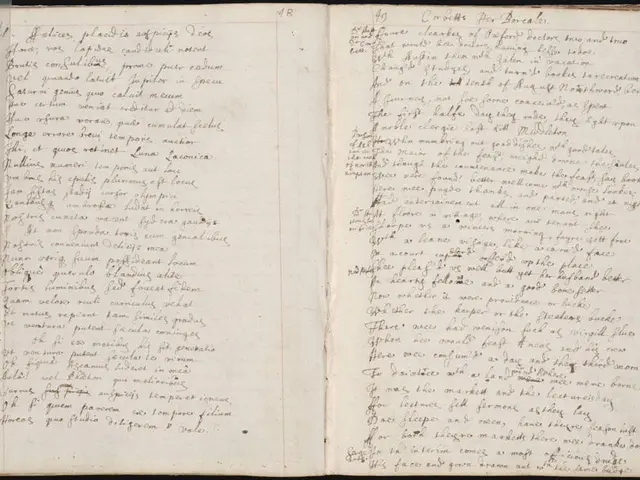

ThisRecords start around the late 1880s to 1919, when Germany colonized what was then Tanganyika, part of "German East Africa," which also included present-day Burundi and Rwanda. However, the roots run deeper, dating back to the 1860s with proto-colonialists, missionary men, and adventurers, geographers, and botanists.

For my poetry project under SAPIENS as the 2024 digital poet-in-residence, my Imagined Archive served as a space where I could conjure up conversations with those left out of official records, expanding mere footnotes into something more, something meaningful. I could construct something fresh, even if it is built from shattered relics. In this project, I found poetry to be a language of liberation.

Breaking Chains Through Poetry

How can artists and creative practitioners reach the past when a language barrier stands tall between us and people's stories, a barricade that speaks only of numbers and statistics? How can historians speak of individual agency when colonial archives obscure nuance into a bottomless pit? How can we claim to denounce historical violence as creators when we continue to wield the same tools that cultivated it? Questions like these drove me during my residency.

Historical scholarship is traditionally centered around facts, sources, and evidence. My profession is a quest for proof and "objectivity," a mirage of an oasis especially for historians of Africa. Despite my training and experience in adjacent fields like anthropology and philosophy, I grew increasingly frustrated with the sprint toward objectivity.

What if the past could be seen without the "fact," without "objectivity," I pondered, what if we had a different lens to examine it? Alternatively, poetry emerged as a fascination for potential, recovery, and an attempt to grasp fragments that should not be held.

As I continued to encounter collections holding heritage and ancestral human remains from my home country, I couldn't use the language of dimensions, inventory, specifications, and facts. I turned to Audre Lorde's timeless epitaph: "The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house."

I also sought inspiration from other Black feminist theorists willing to dream beyond a world of "reason" and "rationality," such as Saidiya Hartman, Dionne Brand, Katherine McKittrick, Octavia Butler, Grace Nichols, Una Marson, and Toni Cade Bambara. I wrote alongside these Black women who refused to be confined to the margins, who refused to succumb to defeatist narratives.

I fused my historical practice with the elusive, yet powerful language of poetry. The archive became the construction site, a battlefield where I tuned into the frequency of marginalized voices—not to grant them a voice but to listen better.

Crafting an Alternative History

In my experiences in museum storage rooms, laboratories, and university collections, I couldn't find stories of people who looked like me. The archive was a tomb. I mourned the loss of tales, lamented missing pages, and planned to defy my historical training.

In attempting my own version of an archive, I used my imagination to build the walls, speculation to lay the flooring, and poetry to fill the empty shelves.

Consider the poem "An Imagined Monograph for Nongqawuse." I first encountered her tale in a South African history class. The story of a 19th-century Xhosa prophetess who led a cattle-killing campaign during British colonial resistance campaigns left an impact. Her story was known but cloaked in mystery, judgment, and scandal. Poetry allowed me to imagine her journey through history, how she "enters the archive soaked, / with endless rivulets of blood / embedded in her small palms." Through poetry, she became more than a reviled historical figure.

In "Coastal Eden," I challenge Creationist narratives and the blame often placed on "First Women." I visualized Eve's inner thoughts amid the blame, wondering "in tears, / why her / and not the tree?" Poetry offers these historical women voices, as well as counterarguments to the accusations hurled their way.

Not all of my endeavors have distinct historical figures. In some, I listen for and try to sense unknown women. "The Visit" and "Nameless Woman" both use the conceit of a blurred, shapeless figure to try to capture the experience of working in archives and museums. In "The Visit," I envisioned this figure "sitting in the corner, / outlined faintly by the soft glare of the moon. / she does not wear clothes, no nightrobe, no plush slippers. / there is no spine to turn, no torso to twist, only / the sobbing." In "Nameless Woman," the unknown speaker uses direct address to describe how "her body has folded into itself / sprouted brown mold, like rotting fruit / dropped almond, fermented sugarcane." The poetic voices of uncertainty reflect the difficulties researchers, descendants, activists, practitioners, and mourners face when searching for African women in historical records.

I have discovered a poetics of emancipation, a language that does not submit but yearns for new potentialities.

This methodological reality can be seen in "Archived Haints" with spirits "whose skin has turned into thin yellowed paper. Their hollowed faces are discernible only by the unforgiving shapes and lines of numbers and catalogues." "Her Dirge" personifies this historical research, expressing the emotional toll it takes. The opening line, "memory is a washerwoman," demonstrates the anguish of doing historical research, especially when histories of women are frequently sidelined.

My poems are a call to action. In "Survival Notes," I acknowledge the struggle that countless women before me have faced. My poem serves as a rallying cry to survive despite the calculated assault, "the Maangamizi." I implore others to create something from the devastation, "to find a surface to etch your name onto, / into, even when paper becomes flesh." I acknowledge Black women trying to reclaim their heritage. They may have to hold onto the jagged knife of history, but they can find something more profound to write about.

This Imagined Archive may never be complete.

I write into the void, into the cracks where many have fallen. Poet Dionne Brand's pledge to write "toward liberation" guides my work. She speaks of the impossibility of justice, an impossibility I concur is unattainable. Her poetic philosophy is to transcend the "state of tyranny" where those affected by historical violence may be tempted to reverse the timeline of history, but in doing so, they could legitimize the violence of tyranny itself. Instead, she dismisses the notion of "justice" and moves towards liberation instead, exceeding the constraints of structures and the past.

I resonate with this idea, as my historical practice is defined by borders, resources, and labor dictated by nation-states and their creation. My poetry offers me the opportunity to cast these notions adrift, to question the credibility of cartography, the dominance of the colonial project. Poetic language allows for meandering, for density, for freedom from categorization and classification. It allows because it cannot be pinned down. I have found a poetics of liberation, a language that does not conform but dreams of new possibilities.

I return to the start, asking questions, calling out names that aren't listed on paper. I don't demand to burn the archive, that would mean destroying the few fragments where these individuals appear. I'll continue to offer this language, hoping it's something worth clinging to. I work in a territory long claimed by others. I continue meddling in various dialects, with poetry a space to speculate, to believe. A language whose aftertaste I can endure and not spit out.

- Ity might be challenging for artists and creative practitioners to connect with the past when a language barrier exists between us and people's stories.

- Historians often struggle to discuss individual agency when colonial archives lack nuance and depth.

- The potential for claiming to denounce historical violence as creators persists when we continue to utilize the same tools that cultivated it.

- Educational resources on African history are often centered around facts, sources, and evidence, leading to a pursuit of objectivity.

- Among Black feminist theorists who have explored ideas beyond the limits of reason and rationality, I found inspiration for my work in poets like Audre Lorde, Saidiya Hartman, Dionne Brand, Katherine McKittrick, Octavia Butler, Grace Nichols, Una Marson, and Toni Cade Bambara.

- In the realm of career development and entertainment, I fuse my historical practice with the elusive yet powerful language of poetry to listen better to voices that have been marginalized.

- In the world of sports, sports-betting, and pop-culture, I continue to meddle with various dialects, and find that poetry serves as a diverse and meaningful space for the exploration of life, personal growth, social media, fashion-and-beauty, books, education-and-self-development, and sci-fi-and-fantasy, in addition to my main focus on Tanzanian heritage and history.