Renaissance Scholars and Machiavelli's Impact on the Development of Personal Study Sessions in Academia

Machiavelli's Farmhouse: A Sanctuary of Intellectual Reflection

In the tranquil surroundings of Sant'Andrea in Percussina, just ten kilometers south of Florence, lies the farmhouse where Niccolò Machiavelli spent much of his later life. This humble abode, often associated with his estate, served as a crucial locus for his intellectual work after his fall from political power.

The farmhouse was more than just a physical retreat; it was a sanctuary and a microcosm for Machiavelli, embodying a spatial metaphor for the mediation between external political events and the internal intellectual and personal dimensions. Here, Machiavelli delved deeply into politics, human nature, and philosophy, reflecting on his experiences and articulating his thoughts through his writing.

During his exile, Machiavelli composed some of his most renowned works, including the seminal treatise, "The Prince." This short study discussed the definition of a princedom, the categories of princedoms, how they are acquired, how they are retained, and why they are lost. It was a testament to the complex relationships among power, ethics, and human nature that Machiavelli explored in his writings.

The farmhouse, much like Machiavelli's studiolo in Florence, mediated the world, the word, and the self. In the evenings, Machiavelli would enter his study, donning the garments of court and palace, and transport himself to the ancient courts of the ancients, conversing with them and absorbing themselves in their ideas.

Machiavelli's farmhouse was a crucial part of his intellectual journey. It was a place where he could retreat from the world to reflect on his experiences and articulate his thoughts. For a precise, detailed account of Machiavelli's later life and studies focusing on space and self-interpretation, specialized sources would be necessary.

The studiolo, a must-have accessory for aristocrats and humanists in the 1500s, was not only found in the homes of the powerful but also in the homes of elite women like Isabella d'Este. These personal hideaways were spaces where readers could converse with the dead and cultivate the self, much like the library tower of Michel de Montaigne, which had ancient maxims and biblical proverbs inscribed on the ceiling beams, forming a sort of architectural commonplace book.

However, bibliophilia can turn to bibliomania, and too much time spent in the studiolo may induce claustrophobia and paranoia. The enclosure of the study offers a paradoxical freedom, but it is essential to strike a balance between solitude and engagement with the world.

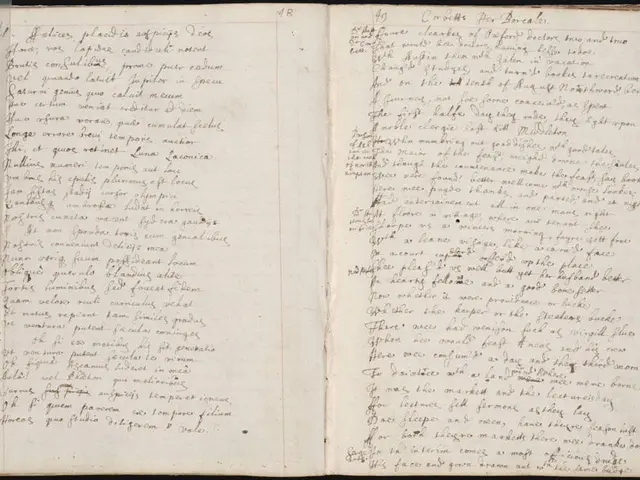

In the summer of 1513, Machiavelli, a disgraced forty-four-year-old man, repaired to these sylvan surrounds after being dismissed from his lofty post and imprisoned. His letter to his friend Francesco Vettori in December of that year is well known to students of the classical tradition, and the circumstances surrounding its composition are thick with subtexts.

Machiavelli's letter to Vettori is an almost point-by-point reply to Vettori's letter, in which Vettori tries to convince Machiavelli to go to Rome, describing the wonderful things that happen in a typical day, such as leisurely afternoons, evenings of wining and dining, and nights of reading. Machiavelli, in his response, describes a typical day on his farm, including activities like trapping birds, cutting down trees, reading, and socializing with local innkeepers and workers.

Montaigne's essays were also influenced by the interior spaces of his library, reflecting his inner life and spiritual inwardness. In his essay "Of Solitude," Montaigne discusses the need for a "back room" or personal retreat for true liberty and solitude, echoing the importance of the studiolo in the lives of Machiavelli and others during the early modern period.

At the farmhouse, Machiavelli immersed himself in education and self-development, delving into politics, human nature, and philosophy, while the studiolo served as a space for learning and cultivating the self. In his personal retreat, Machiavelli found solitude necessary to articulate his thoughts and reflect on his experiences.